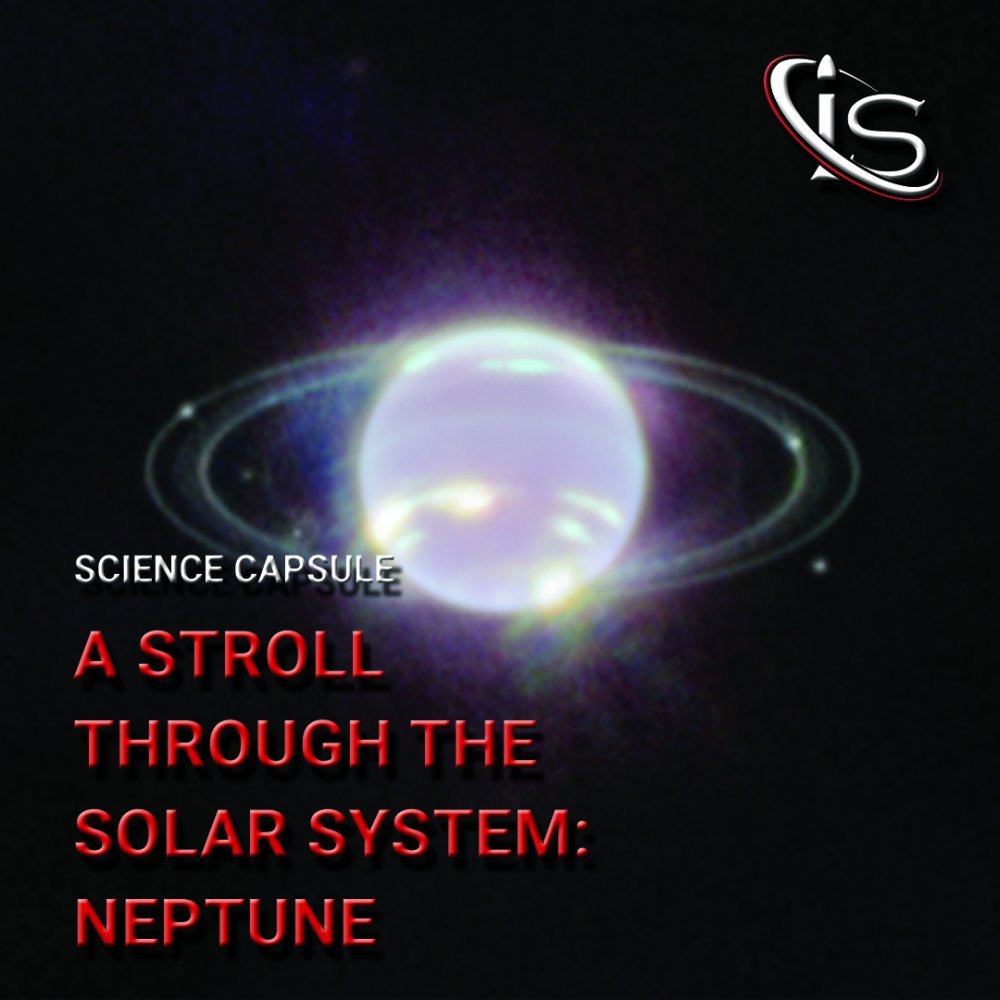

Welcome back to everyone’s favorite planetary series. Today is finally going to talk about the furthest planet from the Sun, Neptune. This is another ice giant and, much like Uranus, has many unique features setting it apart from the rest. There is quite a lot to discuss here, so, without further ado, let’s dive into Neptune!

Ice Giant Part 2: Not a Planetary Boogaloo

To start off this science capsule, I will address the composition of Neptune, as has become customary. As its title implies, Neptune is similar to Uranus, in that most of its mass is made up of “icy materials.” These are the same ones that we discussed for its neighbor: water, ammonia, and methane. They also surround a small, rocky core, once again mirroring the other ice giant.

One key difference here, however, is the density of the planet. Whereas Uranus was the second least dense planet in the Solar System, behind only Saturn, Neptune is the densest of all the gas giants. In fact, Neptune’s rocky core alone is about as heavy as Earth. Another interesting feature that sets Neptune apart is the possible presence of a super-hot ocean underneath its clouds. The water temperature in said ocean would be well above boiling; however, due to the immense pressure on the planet, the water would still not be evaporating.

Just like the other gas giants, Neptune lacks a solid surface. Instead, its atmosphere melts away and blends into the water and icy materials found around its core. Its size is also quite large, with Neptune’s radius being around 24,622 km, coming up just short of Uranus’s radius of 25,362 km.

A Windy Place

Since the planet’s atmosphere was just brought up, we might as well discuss it further here. Just like its neighbor, Uranus, Neptune’s atmosphere is made up of mostly hydrogen and helium, with a dash of methane thrown in for good measure. The methane is what is responsible for Uranus’s signature blue-green color. However, Neptune is a much more intense blue, with no noticeable shades of green. Therefore, it would appear as though something else must be present in this planet’s atmosphere that provides it with this unique color. What that something is remains unclear.

Back in 1989, an incredibly large storm was spotted on Neptune’s southern hemisphere. This was dubbed the “Great Dark Spot” (probably to mirror Jupiter’s Great Red Spot) and could contain all of Earth. The storm has since disappeared, but many more have taken its place throughout the planet.

What is really unique about Neptune is the incredible winds that can be found all over. Not only are they ever-present, but their speeds are quite astonishing, reaching up to 2,000 km/h! To put this in perspective, Earth’s strongest winds only reach 400 km/h (which is more than I would have thought). It is no wonder, then, that Neptune has earned the title of windiest planet in the Solar System.

Time on Neptune

We are back with the time-centered section of our strolls. And, as has been the case for basically all the gas giants, the day and year cycles on Neptune are just a “tiny” bit different than those on Earth.

A Neptunian day is relatively short, clocking in at around 16 hours. This is similar to Uranus, which takes 17 hours to complete a full rotation.

Its year, on the other hand, is by far the longest of any planet in the Solar System. Being 30 astronomical units away from the Sun, Neptune requires a whopping 165 Earth years to complete one revolution around our star. This means that a year on Neptune is equivalent to, approximately, 90337.5 Neptunian days. I can only imagine how frustrating it would be to live on Neptune and experience the holiday season only once in your entire life. Although, it would be quite the substantial season, so maybe there is a silver lining there.

‘Tis the Season

And speaking of, as we are, officially, in November at the time of this stroll’s release, the holiday season is upon us (and I will not hear any arguments against this). It just so happens that Neptune’s rotation axis being tilted by 28° also causes this planet to experience seasons, just like Earth. Well, not quite like Earth, as our seasons are only three months long, whereas Neptune’s last over 40 years. This, combined with the really high pressures found on the planet, makes it very unlikely for Neptune to have the ability to sustain life.

Does that last sentence sound strangely familiar? It should to anyone who read the Uranus science capsule, as it is copied and pasted straight from there. And if you are wondering why I would reuse the same sentence to discuss the possibility of life on Neptune as I did for Uranus, the answer is quite simple. One of the sources I like to check to ensure I do not miss any vital information on any planet is the NASA website. And looking though their pieces on Neptune and Uranus, I could not help but notice that they had the same exact paragraph for the “Potential for Life” section of these planets, with the only difference being the names. So, if it is good enough for NASA, I see no reason why it should not be good enough for me.

The Furthest Planet from the Sun… Kind of

After Pluto’s demotion from planet to dwarf planet, Neptune was officially crowned the furthest planet from the Sun. However, that was not always the case. I am, of course, referring to the good old days of Pluto as a full-fledged planet. Even in that time, however, Neptune would sometimes be the furthest planet from the Sun. This is due to an interesting phenomenon, where Pluto’s extremely elliptical orbit takes it closer to the Sun than Neptune in intervals of 248 Earth years. This strange event lasts for 20 years at a time and only happens between these two planets. Or this planet and dwarf planet, I suppose. Fortunately, due to Neptune’s completion of 1.5 orbits for every Pluto one, the two planets are never at risk of colliding.

Yet Another Bizarre Magnetosphere

Neptune’s magnetic field axis shares a common trait with its neighbor Uranus, in that it is tilted away from the planet’s rotation axis. And while the 60° difference between the two axes on Uranus is still greater than Neptune’s difference of 47°, Neptune’s magnetosphere still shifts constantly due to this misalignment. Furthermore, much like every other gas giant, Neptune’s magnetosphere is much stronger than Earth’s. 27 times stronger, in fact.

The God of the Sea

Welcome to one of my favorite recurring segments, the mythological origins for a planet’s name. Today we have Neptune, whose name comes from the Greco-Roman deity of the sea. Together with Jupiter, god of the sky, and Pluto, god of getting the short end of the stick, I mean the underworld, Neptune is one of the big three. And yes, this is a reference to the Percy Jackson series. I could go on and on about this deity, as he is one of my favorites in all of mythology; however, this is not a stroll through history and literature, but rather one through the Solar System, so I better stop here.

Before moving on, I would just like everyone to appreciate this very apt name. Not only is Neptune blue in color, making it the ideal planet to name after the sea god, but its name is also the Roman version of a character from the Greco-Roman myths, something that should be true for every planet and moon in the Solar System. And fortunately, unlike Uranus, this same naming convention applies to this ice giant’s satellites.

Neptune’s Moons

Just like all its gas giant companions, Neptune is host to a sizeable number of moons. 14, to be precise. While this is much less than planets like Jupiter and Saturn, it is still more than any of the terrestrial ones.

As I alluded to previously, Neptune’s moons are all named after Greco-Roman mythological characters. To get even more specific, this planet’s moons take their names from various nymphs and lesser sea deities. One such example is the largest moon orbiting Neptune, Triton. This name is, once again, perfect. Not only is Triton a lesser sea god, but he is the son of Poseidon and Amphitrite, making him the perfect candidate to give Neptune’s grandest moon its name. And for anyone wondering why I temporarily switched to the Greek names, the reason is that Amphitrite’s Roman counterpart is a much lesser deity than the original Greek one. Therefore, it did not feel right to use the Roman name when describing the ancestry of the mighty Triton.

There is more to this moon that I want to discuss, but, as I am planning to have dedicated strolls to the major moons of the Solar System, I will leave that topic to future me.

Neptune’s Rings and…

As has become tradition with these gas giants, we are going to have a dedicated section to Neptune’s ring system. This planet is host to 5 rings; however, there is one particular trait that is not observable on any other planet. That trait is the presence of 4 prominent ring arcs in Neptune’s ring system. So let’s take this one step at a time, starting with the rings.

Moving from the closest to the furthest away from Neptune, the rings are Galle, Leverrier, Lassel, Arago, and Adams. As the keen observers among you may have noticed, these names have a distinct French flavor to them. While this is straying away from the Greco-Roman naming convention, that was always more for planets and moons than rings, so I approve of this naming scheme (especially when compared to the mess of names that is Saturn’s ring system). These rings are also thought to be relatively young, thus setting them further apart from those around other planets.

Neptune’s Arcs?

The ring arcs, on the other hand, are clusters of dust that are present in the largest ring, Adams. What is extremely peculiar about this is that, according to the laws of motion, these arcs should not be clumped together like this and should, instead, be spread out. However, scientists have recently theorized that these clumps exist thanks to the influence of one of Neptune’s moons, Galatea, which is just inside of the Adams ring. Incidentally, Galatea has two main mythological origins. The first is related to an ivory statue made by Pygmalion of Cyprus, which was said to have come to life in Greek mythology. The other has to do with the love interest of the cyclops Polyphemus. Since Polyphemus is a son of Poseidon, I am more inclined to think that the second origin is the one referenced in the moon’s name.

To finish this section off, let’s go through the names of said arcs. They are Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité, and Courage. I was about to go on a rant regarding the baffling choice of having four French names and one English one… but I then looked up the French word for courage and found out that it is, in fact, courage.

Another Stroll Bites the Dust

We have come to the conclusion of yet another stroll, and so it is time to end it in style with one final fun fact. Unfortunately, that fun fact is the same as the one I used to conclude the Uranus science capsule. That being how both planets are believed to have formed much closer to the Sun than where they, currently, reside. Even if I were to use my alternative fun fact about Voyager 2 being the only spacecraft to have visited Neptune, I would still be repeating myself from the Uranus stroll. Alas, my hands are tied.

Unless… of course! My good old friend math is here to save the day. And that is because Neptune was actually predicted by mathematical means before being ever discovered. Thank you, math! You really are infallible.

And now, we truly are at the end of our stroll. If you enjoyed learning about this planet (and some Greco-Roman myths along the way), I recommend checking out our other science capsules on the Solar System. And if you would like to stay up-to-date with all the newest strolls, then you need only check back here, at impulso.space, every Wednesday. Next week is the culmination of our planet-oriented capsules, so I suggest staying tuned for that.