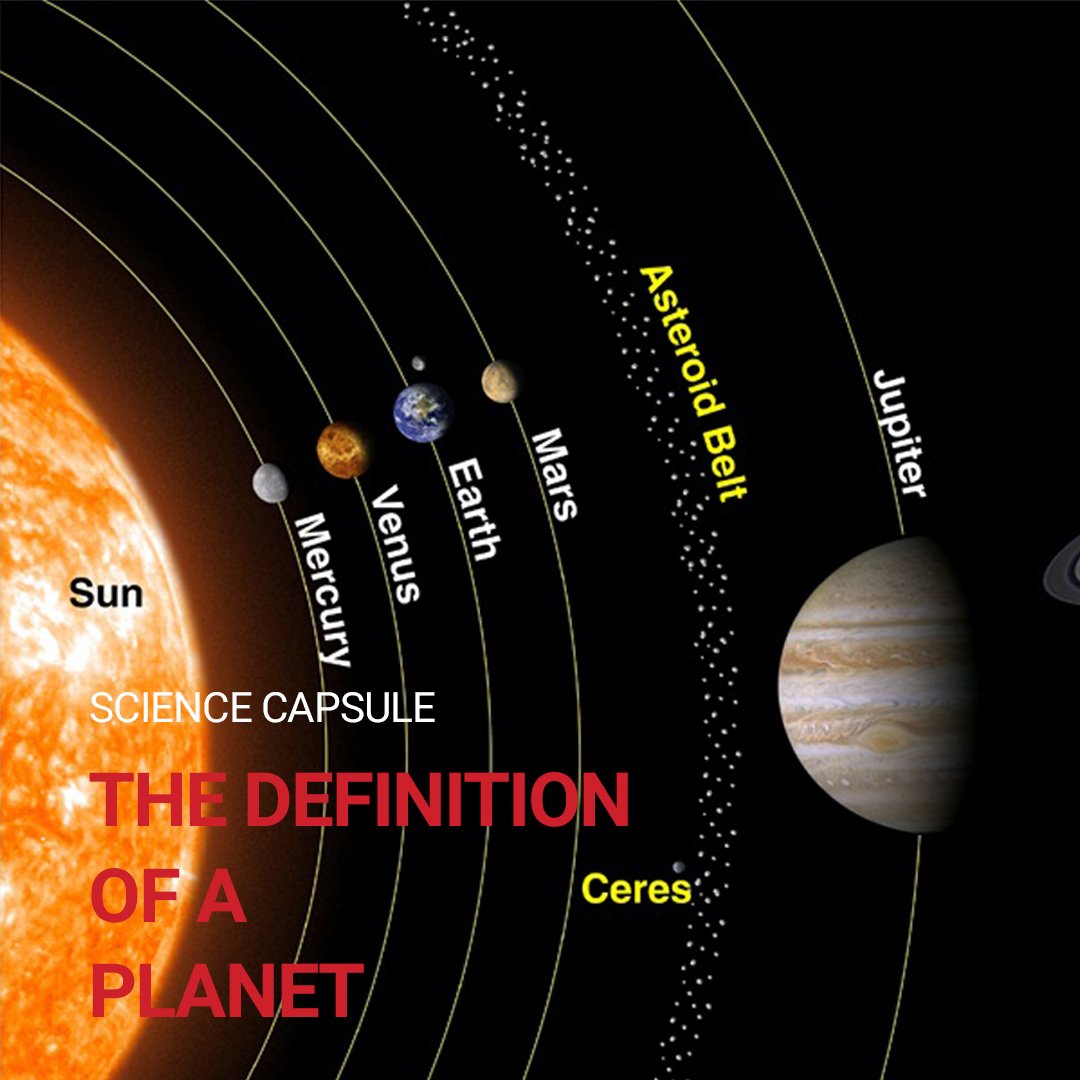

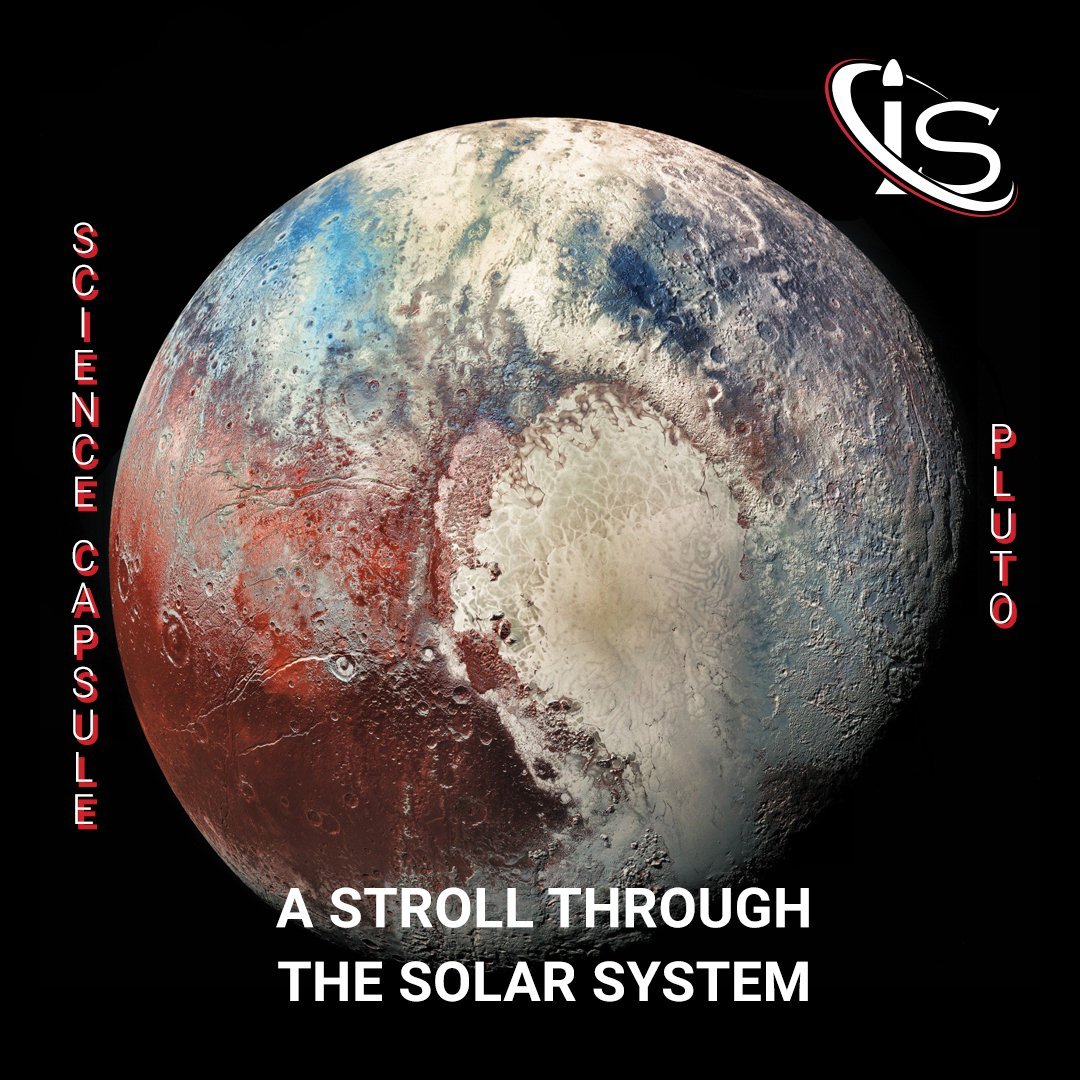

Welcome back to another stroll through our galactic neighborhood. Today, we will talk about one of my personal favorite celestial objects around, the dwarf planet Pluto. Most people probably know this as the planet that was but no longer is; however, I am here to tell you that there is much more to this icy rock than an unfortunate category demotion. Before going any further, I should mention that this stroll will not focus on the nuances behind Pluto no longer being a planet. That topic is quite lengthy and something we covered in a previous science capsule, “The Definition of a Planet”. Anyway, without further ado, let’s talk about what used to be the farthest planet in the Solar System.

Smaller Than the Moon

Pluto is well-renowned for holding the title for smallest planet in the Solar System — until it stopped being one, of course. However, this rock is so tiny that even our Moon exceeds it in size. Coming in at a mere 1,151 km, Pluto’s radius is only around 2/3 that of the Moon. Furthermore, due to its composition, its mass is a tiny 1/6 that of our satellite. This is because Pluto consists of a rocky core and water ice mantle, with other ices, like nitrogen and methane coating its surface. Meanwhile, the Moon is made up entirely of rock.

Far Far Away

I will let everyone reading decide whether this title is Star Wars or Shrek related. Just know that I will not confirm one way or the other. In any case, Pluto sits at an average distance of 5.9 billion km from the Sun, which is about 39 AU (astronomical units). Due to its orbit, this number will actually vary greatly, but we will delve into that more, shortly.

The main effect that this distance has on the planet is the way Pluto interacts with the light coming from the Sun. Not only does a photon from our star take 5.5 hours to reach this remote dwarf planet, but the lengthy trip greatly diminishes the amount of light hitting it. Compared to Earth, the brightness of the Sun as seen from Pluto is 900 times less. Interestingly enough, however, there is a point during the day here on Earth when the sunlight observed is just as bright as it is midday on this faraway object. This happens closer to sunset and is something that you can look into for your area.

If you would like to do that, NASA has an entire tool dedicated to this. Simply look up “Pluto time on Earth” and it should come up. The one in my area at the time of writing this article is 7:36 pm. After saying all this, I feel like I should disclose that we are, in fact, NOT sponsored by NASA.

Time on Pluto

It is, once again, time (pun very much intended) to discuss how days and years pass on Pluto. Let’s start this off with the Plutonian year. To no one’s surprise, Pluto has the longest year of any planet in the Solar System. Although, I suppose that is no longer relevant, given its downgrade to dwarf planet. Still, it takes Pluto an incredible 248 years to complete a singular revolution around the Sun. To put this in perspective, the farthest “actual” planet in the Solar System, Neptune, has an orbital period of 165 years. Which is still only 2/3 of the time it takes Pluto to complete one revolution.

Another interesting aspect of Pluto’s orbit is its ellipticity. Because of how “stretched” and oval-shaped its path is, Pluto at perihelion — the moment an object is closest to the Sun during its orbit — sits closer to our star than Neptune. This last happened between the years of 1979 and 1999. For anyone curious, Pluto’s perihelion distance from the Sun is 30 AU, while its aphelion one is 49.3 AU.

Pluto’s Backwards Day

Moving on to the Plutonian day, there are a couple interesting features that set it apart from other celestial objects. First, Pluto rotates in retrograde motion, or East to West. This is the opposite of most planets and moons but is not a trait that is unique to this icy rock. Long time followers of our blog might remember that both Venus and Uranus exhibit the same type of motion. Although, Uranus’ axis is so tilted that it almost looks like a South-North rotation instead. That is not the case, of course, as its axis is what determines the cardinal directions, but it is an interesting phenomenon that is fun to remember, nonetheless.

And speaking of tilted axes, Pluto’s is not exactly upright. While it is nowhere close to the 97.7o tilt of Uranus, Pluto’s axis still sits at a comfortable 57o. This implies that the dwarf planet experiences seasons; however, these all consist of cold or even colder weather, as the temperatures here average -232o C. Another interesting point is that it takes Pluto around 153 hours to complete one rotation, making its day fairly long. This also means that there are “only” 14,199 Plutonian days in a Plutonian year, as opposed to 90,520 terrestrial ones.

Geology Break(s)

Let’s now discuss the surface of this remote dwarf planet. Like we saw before, Pluto is mostly covered in various types of ice, with water, methane, and nitrogen being some of the most prevalent. Furthermore, mountains, valleys, plains, and craters pepper its surface. The mountains can reach 2-3 km in height and are mostly water ice. The valleys on Pluto can also be quite large, with their length reaching 600 km.

But perhaps the most interesting part — at least for fellow geology aficionados — is the craters. These can be quite large, with some coming in at 260 km of diameter; however, the really intriguing characteristic they have is showing signs of erosion and filling. This type of weathering of Pluto’s surface would indicate the potential presence of tectonic movement on the dwarf planet. If that were, indeed, the case, Pluto would join the relatively exclusive club of currently geologically active objects in our Solar System.

The last feature that can be observed on this dwarf planet’s exterior is its plains. These appear to be made of frozen nitrogen gas and do not exhibit any craters. However, these plains do have structures that suggest convection is taking place.

Could Life Survive on Pluto?

Short answer: no. Long answer: maybe, on the inside, close to the core, where the water ice could potentially be turning into a water ocean due to warmer temperatures, life could, theoretically, potentially, supposedly exist… but probably not.

A Changing Atmosphere…

Pluto has a very interesting phenomenon occur in its atmosphere. Something that has not really come up in any of the previous strolls. As it approaches the Sun, Pluto’s atmosphere is constantly getting bigger, with the opposite being true as the dwarf planet starts getting more distance from our star. The reason behind this is that, as its proximity to the Sun increases, more and more of the frozen gases on its surface will start to sublimate — meaning they will turn from a solid to a gaseous state. This, in turn, increases the size of the atmosphere. Something that gets only exacerbated by the low gravity, as that allows it to extend in altitude even more.

On the other hand, as the small planet moves away from the Sun, its temperatures will drop even further, causing the atmosphere to precipitate back down in snow-like fashion. As for what materials make it up, they are the same one as the frozen gases found on Pluto’s surface, with nitrogen accounting for the bulk of it, and methane and carbon dioxide making up the rest.

And a Nonexistent Magnetosphere

I like to have the atmosphere and magnetosphere sections follow one another — an idea which I definitely did not steal from NASA’s website. However, there is not a whole lot to talk about here, as Pluto’s slow rotation and small size would suggest a lack of any noticeable magnetic field originating from it. This is not confirmed yet; but, even if it did turn out to have some type of magnetosphere, the size of it would have to be pretty minimal.

Pluto and the Kuiper Belt

Even though this is not the focus of the capsule, it is still a good idea to briefly explain why Pluto is no longer considered a planet. One of the requirements for being a planet is not having other celestial objects of similar size in the vicinity. Pluto, unfortunately, does not meet that criterion. That is because, over in Pluto’s “neighborhood”, other similarly-sized dwarf planets exist. And all of these — together with Pluto — constitute the Kuiper Belt.

However, just because it is no longer a planet, that does not mean that Pluto is without moons…

Pluto’s Crew

Even with its diminutive size, Pluto has five moons orbiting it. These are: Charon, Nyx, Styx, Kerberos, and Hydra. For anyone familiar with Greek mythology, those are all names of figures (or landmarks) connected to the Underworld. Fret not, we will explore these more in the reoccurring mythological origins section, which is coming up next. However, it is important to talk about what the moons themselves are like, particularly Charon.

First, let’s discuss the other four. These are all fairly small moons — otherwise they would not be orbiting Pluto — and have the distinguishing feature of not being tidally locked to their (dwarf) planet. This means that they will not have the same side constantly facing Pluto, setting them apart from many other moons in the Solar System. They are also not spherical but rather irregular in their shapes.

Charon, on the other hand, is basically the opposite of the other Plutonian satellites. It is spherical, tidally locked to Pluto, and orbiting at the same 153-hour period as the length of its planet’s day. That last trait is particularly interesting, as it means that Charon neither sets nor rises over Pluto. Furthermore, Charon is half (yes half!) the size of its host planet. This makes it the largest moon in the whole Solar System when compared to its planet, even beating the Moon-Earth ratio of 1:4. It also orbits at a mere 19,640 km from Pluto, which is about 1/20 of the distance between us and our own Moon.

Mythological Origins and a Unique Naming History

As always, it is time to wrap up this stroll with the one and only mythology section. However, there is something else that I want to bring up, first. Pluto has the very unique honor of being the only planet (dwarf or otherwise) named by a young girl. And by that, I do not mean young adult. Nope. Pluto was named by an actual child, the 11-year-old Venetia Burney. Now, this was only possible because of her grandfather, sure; but the idea to name the planet after the Roman god of the underworld was all hers. That is pretty cool, if you ask me.

Pluto: The Unluckiest God Around

Anyway, onto Pluto’s origins. As I just said, the planet takes its name after the Roman version of Hades, the Greek god of the Underworld. The main thing to know about him is that he always gets the short end of the stick. Not only does he get stuck living underground and regulating the passing of souls while his brothers are partying on Mount Olympus and/or in the Ocean, he also gets a bad rep because of this. I suppose it makes sense. Greco-Roman deities are largely flawed, so how could the “god of death” not be the worst of the bunch.

But, in actuality, he is one of the few who is faithful to his wife — at least in most myths — is not as petty as his brothers, and is generally fair in his rule of the Underworld. Sounds a lot better than most of his relatives, if you ask me.

And yet here he is, thousands of years later, needing the innocence of a child to get his own planet. A planet, which has now been deemed unworthy of such a prestigious title. The dude really cannot catch a break. It is a good thing he is not real, otherwise I fear what he might be tempted to do to the Underworld as punishment for mankind.

The Silver Lining

The one good thing Pluto has going for him is that the other deities and creatures working with him are similarly trustworthy. So, let’s just quickly go through the ones that give the moons their names. Charon is the ferryman of the Underworld who escorts dead souls on his boat through the river Styx. Nyx is the goddess of night and mother of other important deities, such as Hypnos, god of sleep, and Thanatos, god of death (remember Pluto is the god of the Underworld, not death itself).

Kerberos is the three-headed dog guarding the entrance (and exit) to the underworld, and Styx is the aforementioned river. The only one left is the hydra, the serpent with regenerating heads that Hercules — Iraklis if we are using the Greek name — faced. This is the only one that is not necessarily a trusted member of Pluto’s crew; however, that is in large part due to the fact that it is not truly an intelligent creature. More of an additional security measure.

Anyway, that will do it for this installment of “Strolls Through the Solar System”. I hope you enjoyed reading this as much as I did writing it. Next week will be a pseudo sequel to the technical capsule on satellite photography. Except it will focus on TV channels, and how satellites can transmit different frequencies worldwide. “See you” next Wednesday, right here, at impulso.space.