Welcome back to another entry in our space programs series. So far, we have discussed the Moon, Mars, and Venus missions. It seems only right, then, to tackle the last of the rocky celestial bodies close to our Sun, Mercury. But, unlike all the other programs we have explored so far, the closest planet to the Sun does not have numerous missions centered around it. In fact, there have only been two missions that reached Mercury in the history of the space industry.

Although, there is another one that has already launched and is poised to arrive at this planet in 2 years. In any case, today will not be about choosing and showcasing the most important Mercury missions. Instead, we will discuss every mission ever sent here and its significance. So, without further ado, let’s delve into the Mercury Space Programs (not to be confused with the entirely separate Project Mercury).

Mariner 10

As always, we are going to tackle the missions in chronological order. And, given how only three agencies have ever sent spacecrafts to Mercury, we will not divide these missions based on any one program. With that being said, first up is Mariner 10.

Part of NASA’s Mariner program, Mariner 10 was the first ever mission sent to the (now) smallest planet in the Solar System. Launched on November 3rd, 1973, from Cape Canaveral, this mission explored our neighbor Venus, before going on to reach Mercury. This was done for two reasons. One, gather more data about Earth’s twin — which was also the subject of other Mariner missions. Two, to help Mariner 10 reach Mercury’s orbit.

The King of Firsts

And this brings us nicely to what Mariner 10 was able to accomplish. By using Venus’s gravity, this became the first spacecraft to use a planet’s gravity to reach a second one. Of course, this was also the first time a spacecraft reached Mercury. But its list of firsts does not end there. Mariner 10 was also the first time a spacecraft used the solar wind as a means to orient itself.

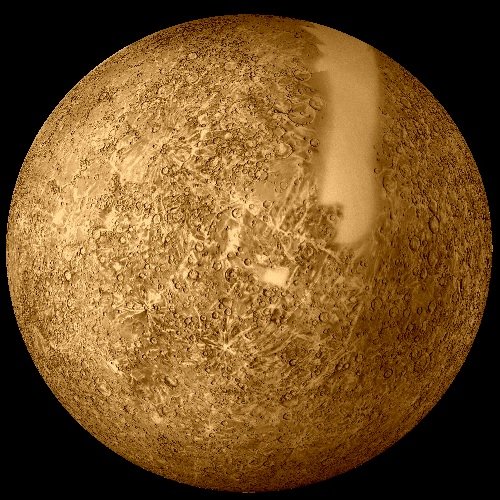

It was also the first time a spacecraft returned to its target after initially reaching it. Not only that, but Mariner 10 went back to Mercury for a third flyby before being decommissioned, not just a second one. And, on almost the opposite end of the spectrum, this also ended up being the last Mariner mission. Although, originally, two more were planned, they were recommissioned as Voyager 1 and 2. And as for the data it collected, the transmissions from Mariner 10 allowed scientists to reproduce the following image of Mercury. For anyone curious, that smooth band is a part of the planet that was not explored by this spacecraft.

The mission then ended on March 24th, 1975, over a year and 4 moths after its launch.

MESSENGER

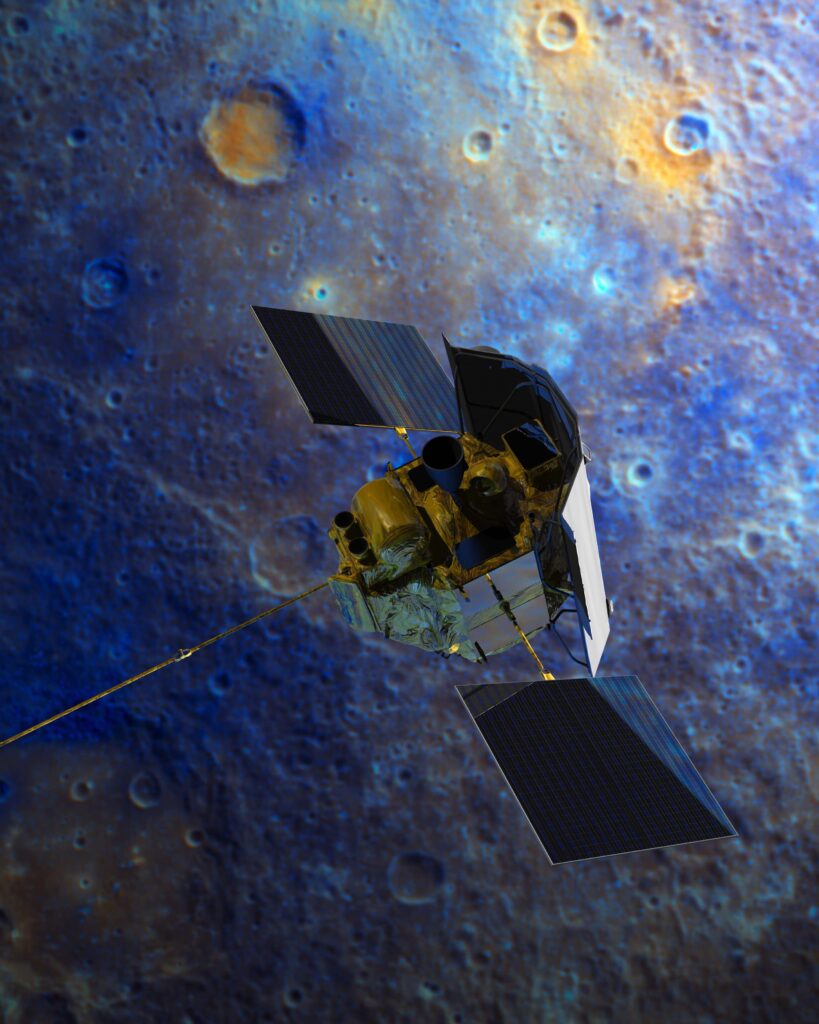

Next up is the only other mission to have ever made it to Mercury (so far). And that mission’s name is MESSENGER. Launched by NASA on August 3rd, 2004, from Cape Canaveral (shocking, I know), MESSENGER was the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury, as opposed to just doing flybys of it. The main idea behind this mission is given by its acronym, Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging. Indeed, the main goal for MESSENGER was uncovering more information about Mercury’s geology, chemical composition, and magnetic field. It was also part of the Discovery program, becoming its seventh mission.

MESSENGER’s journey to the Solar System’s innermost planet featured a concept we just explored. Using planet’s gravities to aid in reaching its destination. However, unlike Mariner 10, one flyby of Venus was not enough to accomplish this. The reason for this is that entering Mercury’s orbit requires avoiding being thrown off course by the increased gravitational pull that comes from flying so close to the Sun.

In fact, MESSENGER required a total of 6 flybys to enter Mercury’s orbit. First, one of Earth (Aug. 2nd, 2005), then, tow of Venus (Oct. 24th, 2006, and Jun. 5th, 2007), and, finally, three of Mercury, itself (Jan. 14th, 2008, Oct. 6th, 2008, and Sept. 29, 2009). Furthermore, these flybys provided data about the planets they were centered around, as well. The Earth one led to beautiful pictures of our planet and satellite, while the Venus one coordinated its data with the simultaneous Venus Express mission from ESA to learn more about our neighboring planet.

After these flybys, it was finally time for MESSENGER to enter Mercury’s orbit. Although the journey was long and complex, on March 11th, 2011, it was finally completed.

Uncovering Mercury

On April 4th, 2011, MESSENGER’s mission of collecting data on Mercury was officially underway. From that day to March 17th, 2012, this spacecraft took almost 100,000 images of the planet’s surface. This included the following image which showcases all of our system’s planets, bar Uranus and Neptune. During this time, MESSENGER also discovered large deposits of magnesium and calcium on the planet’s northern nightside, something which causes Mercury’s magnetic field to shift towards that part of the planet. On top of this, MESSENGER’s first mission showed evidence of past volcanic activity and the presence of vast amounts of water in Mercury’s exosphere.

Going Above and Beyond

Some of you may have noticed I said, “first mission”. That is because the MESSENGER mission was extended twice after this. The first extension lasted one year, ending on March 17th, 2013. It was during this time, around May of 2012, that MESSENGER had mapped all of the planet’s surface, both in monochrome and color. This period also saw the discovery of frozen water ice close to Mercury’s poles. While that may seem counterintuitive at first, the cause of this has to do with Mercury’s tilt being close to 0, which leads to almost no sunlight reaching these areas. Still, it is kind of amazing that not just ice, but water ice, can be found on the planet closest to the Sun.

As for the second and final extension, its duration took the MESSENGER mission all the way to March 2015. Furthermore, in order to continue the mission, two orbital maneuvers were executed to raise the altitude of MESSENGER’s orbit, which had fallen to a mere 25 km (15.5 mi). Then, on January 21st, 2015, one final maneuver was executed to enable the spacecraft to last until spring. Finally, on April 30th, 2015, MESSENGER crashed onto Mercury, after depleting its fuel two weeks earlier on the 15th. And, in the process, it created a new crater on the planet.

BepiColombo

Named after the Italian scientist Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo this mission launched on October 20th, 2018, from Centre Spatial Guyanais. Contracted by Arianespace, the rocket used for this launch is one that just recently launched for the last time, Ariane 5. This mission is still ongoing, as none of the spacecraft’s components have reached their target destination, yet. So, there is not as much to say about what it has accomplished, since that still has to unfold.

However, we can still explore what the mission objectives are. First off, the BepiColombo mission consists of 3 separate spacecraft components. They are: the Mercury Transfer Module (MTM); the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO); and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) also known as Mio. The first two were built by ESA, while the last was constructed by JAXA. With an expected arrival in Mercury’s orbit of December 5th, 2025, the MPO and Mio satellites will collaborate to examine the planet for one year. Although, there is the possibility of a one-year extension. Also, for anyone wondering, many flybys of other planets are included in this path to Mercury, as the same problem that MESSENGER faced will (and already has) resurface(d) for BepiColombo.

What Can We Expect?

The goal for the mission is to characterize and determine the size of Mercury’s solid and liquid core. Furthermore, this mission aims to deepen our understanding of the planet’s exosphere, magnetosphere, and composition of the water ice craters located at the poles. It also will try to verify Einstein’s theory of relativity by measuring the gamma and beta parameters. That is a very big oversimplification, since getting bogged down into the meanders of general relativity is not today’s goal. However, we have done a capsule covering this topic before, titled, “How Does Time Pass on Satellites?”. So, you can check that out if this subject fascinates you as much as it does me.

Until Next Time

That will do it for us today. I hope you enjoyed learning more about what missions have been centered around the innermost planet of the Solar System. And, since I never stated this outright, I will explain why there have been so few, now. The problems that the Sun’s increased gravitational pull introduces when you get that close to it are no small matter. Couple that with a longer distance than visiting Venus, Mars, or, of course, the Moon, and Mercury is not in the best spot to be explored by us. Still, the missions that have gone there have already yielded good results, and with BepiColombo on the way, I see no reason why we cannot continue to uncover this planet’s inner workings.

In any case, if you enjoy the content we provide, make sure to tune back in next week for our next Historical Milestone. “See you” all then, right here, at impulso.space.