Welcome to a new science capsule everyone, and the first of the new year no less. Given this is the official kick-off of science capsules in 2024, I wanted to come up with a fun idea for it. After racking my brain for a couple days, I had a sudden realization: we have never discussed galaxies on here. Well, that all changes today, as, finally, we tackle one of the most important topics related to space. There is quite a lot to unpack, so let’s get straight to it.

What Is a Galaxy?

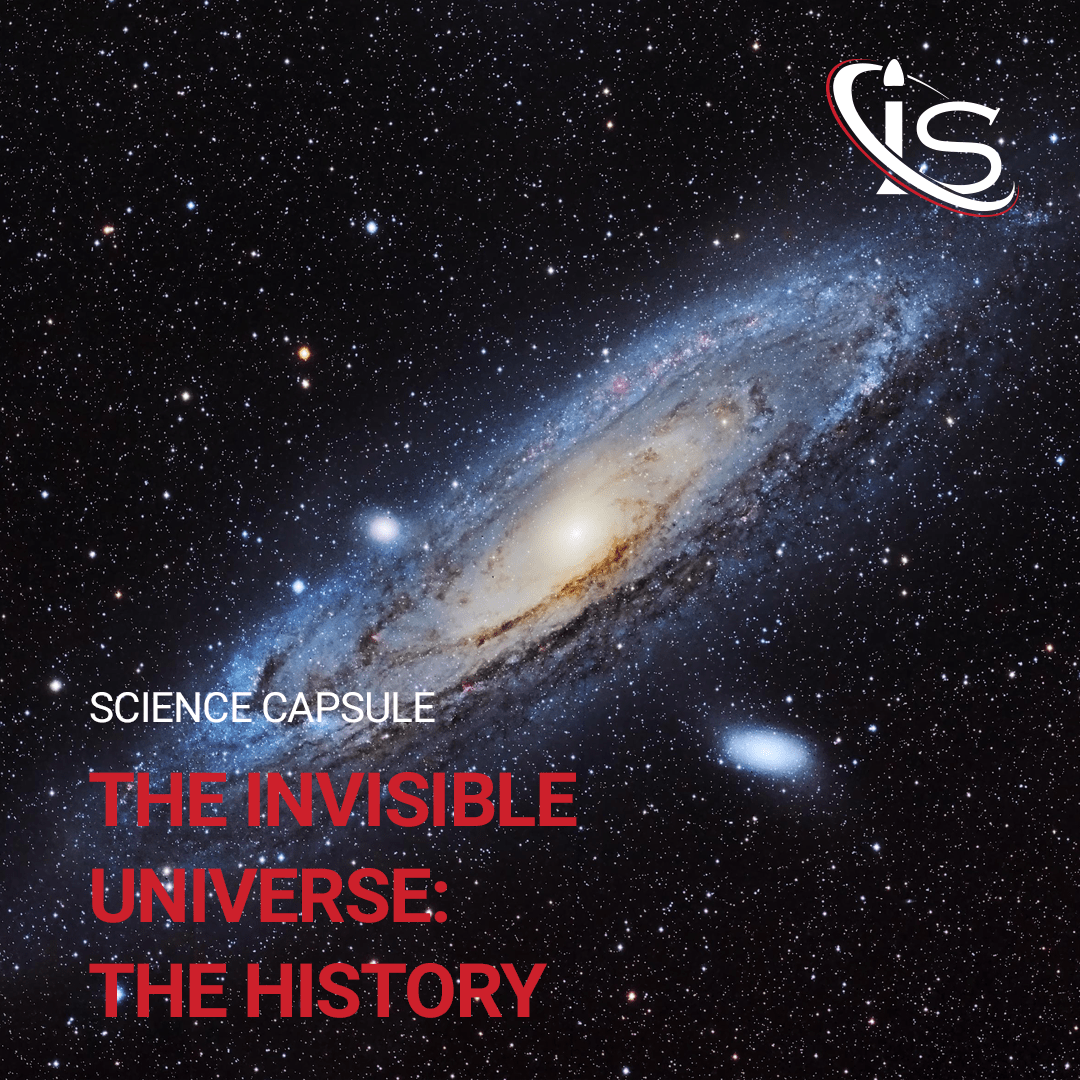

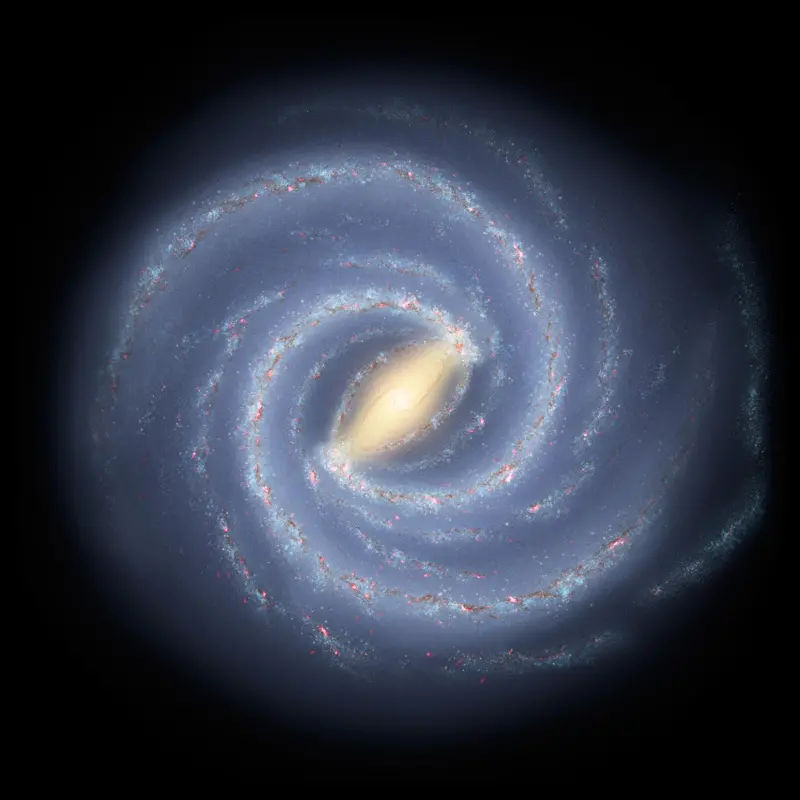

The basic definition of a galaxy is both simple and slightly vague. Well, perhaps not vague as much as very broad. In essence, a galaxy is any cluster of stars, planets, gas clouds, and other celestial objects/systems that are gravitationally bound together. This, of course, includes our very own Milky Way, which is a spiral galaxy — a concept that will be explored later.

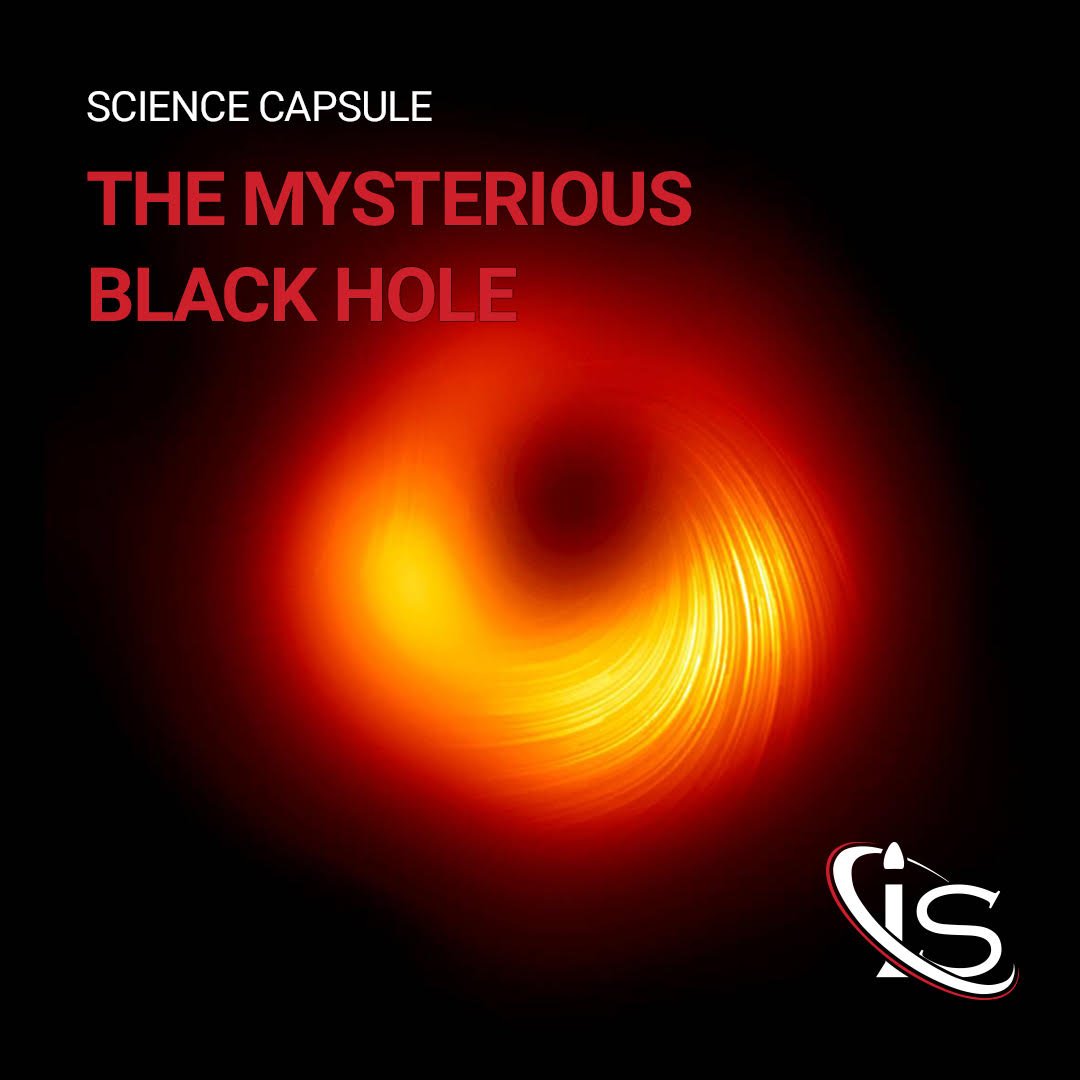

Another feature that most galaxies have in common is a supermassive black hole. These behemoths are located at a galaxy’s center and are often the main source of the gravitational pull holding everything together. These are not — as far as we know — strictly necessary for a galaxy to form. However, they appear to be quite common, with both the Milky Way and its neighbor, Andromeda, having said black holes at their center. Little fun fact here about our galaxy: the black hole in the middle of it is called Sagittarius A. However, I think the Milky Way deserves its own article, so let’s get back to talking about galaxies as a whole.

To give an idea of how massive some of the objects in a galaxy can really be, we need only look at Andromeda’s black hole. This comes in at a staggering 140 million solar masses, which is hard to even fathom. This is also large by supermassive black holes standard, as our own is “only” 4.3 million solar masses. The discrepancy is due to a variety of factors, with the density at the center of Andromeda being greater than that of the Milky Way’s standing chief among them.

How Old Are Galaxies?

As many of you may already know, galaxies are, generally, among the oldest structures in the Universe. But just how old are they? Of course, there is no one standard answer. The range is as large as the age of the Universe. Well, almost. While some galaxies are much younger than the rest, the most recent one discovered, so far, is still 500 million years old. Meanwhile, on the other end of the age spectrum, the oldest galaxies detected have been around for 13.8 billion years — almost as old as the Universe, itself. The most common range, however, appears to be between 10 and 13.6 billion years old.

Galaxy Clusters vs Galaxy Groups

For anyone interested in the vast (pun intended) field of space, the term galaxy cluster is probably nothing new. However, this is not the only type of galaxy ensemble present in the Universe. There are two more, in fact. One is known as a galaxy group, and it comes with a simple difference when compared to a cluster. The other is a supercluster, which, while sharing part of its name with galaxy cluster, is, somewhat deceptively, the most different.

Starting with groups, and their difference to clusters is very straightforward: the number of galaxies inside it. While clusters have thousands of galaxies held together by their mutual gravity, groups “only” have hundreds. Superclusters, on the other hand, are almost a completely different entity. That is because, unlike a cluster or a group, they are not held together by gravity. Instead, they usually consist of regions that exhibit both clusters and groups in close proximity to each other.

Types of Galaxies

There is one more, rather large, area to cover when it comes to understanding galaxies: the different types. Each one of these could deserve a capsule all to itself, but I would be remiss to do a piece on galaxies without at least giving them a brief overview.

Spiral Galaxies

Probably the most famous type, in large part due to the Milky Way falling under this category, is the Spiral Galaxy. Characterized by spiral arms, these galaxies have a rotating disk of stars on the outside and a central bulge with a higher concentration of stars in the middle. Other than the Milky Way, its neighbor Andromeda is another example of a spiral galaxy. Particularly, they are barred spirals, meaning they have ribbons of stars, dust, and gas cutting through their centers.

Elliptical Galaxies

Less common than spiral ones, Elliptical Galaxies do not exhibit any particular organization. Although, as the name suggests, their overall shape ranges from very elliptical to circular. The stars here are usually older than those in Spiral Galaxies. This is due to limited gas and dust, which are the main ingredients needed to make new stars.

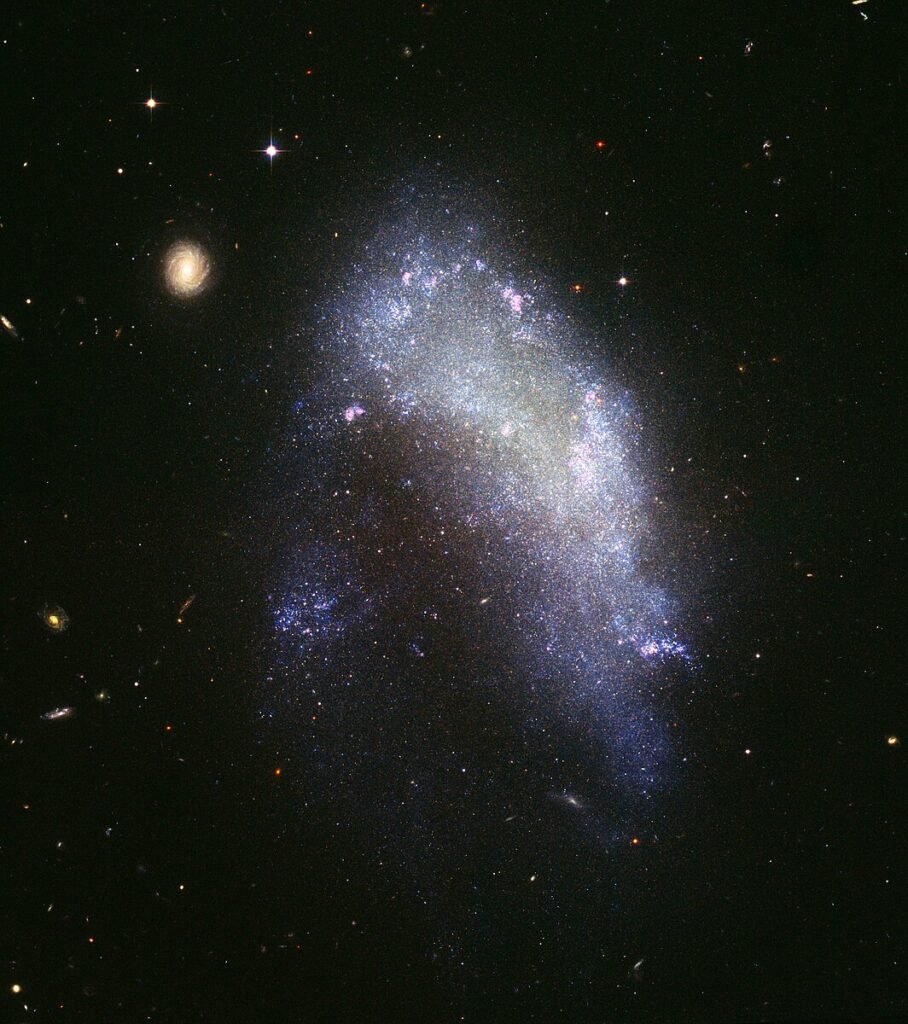

Irregular Galaxies

Speaking of lacking organization, Irregular Galaxies do not have a “standard” shape. Ranging from rings to just groupings of stars, these are believed to form due to interactions with other galaxies. Some of the larger ones are even theorized to be an in-between of elliptical and spiral galaxies.

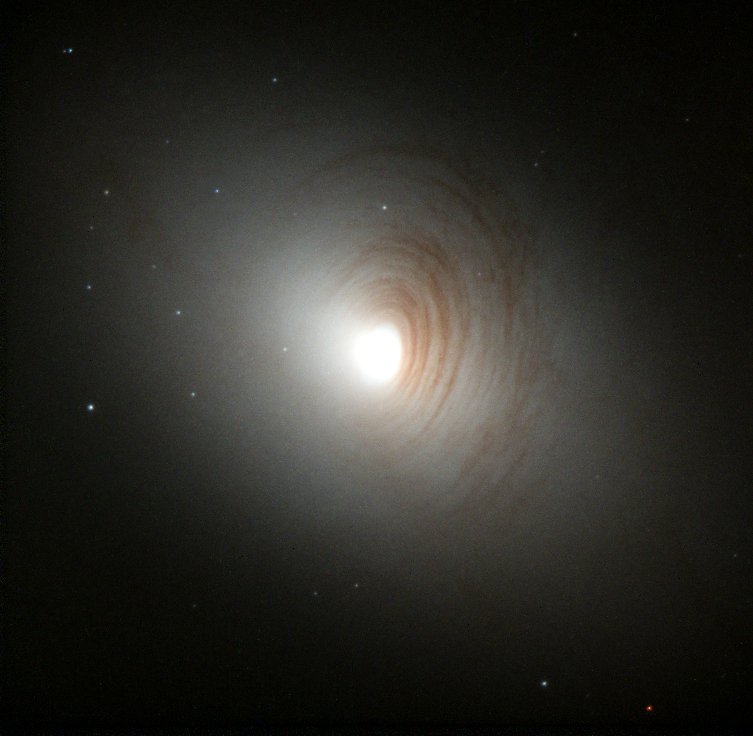

Lenticular Galaxies

These galaxies appear closest to a mix of spiral and elliptical ones. They exhibit a central bulge, like Spiral Galaxies, but lack any spiral arms. Furthermore, they do not have many young stars. This is because — much like Elliptical Galaxies — they are lacking in gas and dust concentration.

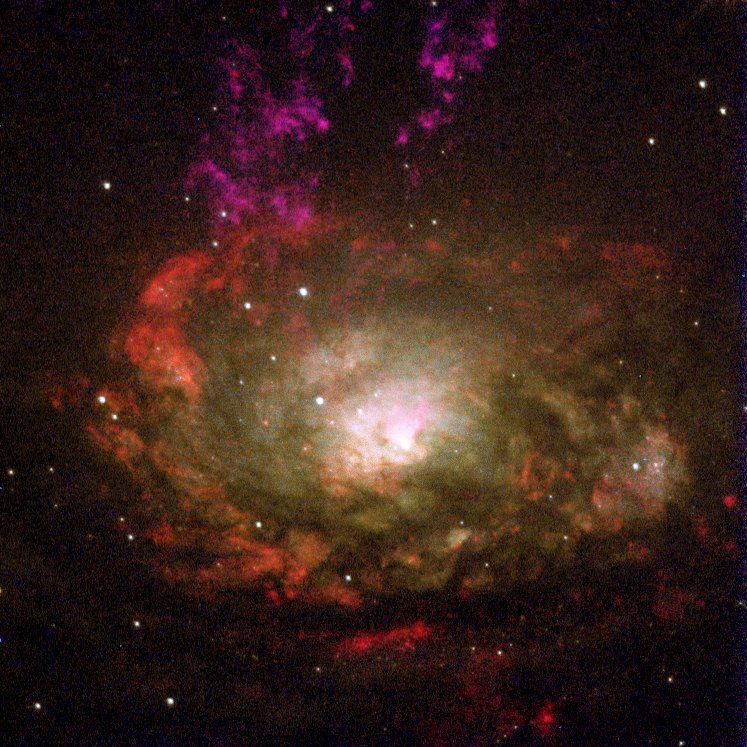

Active Galaxies

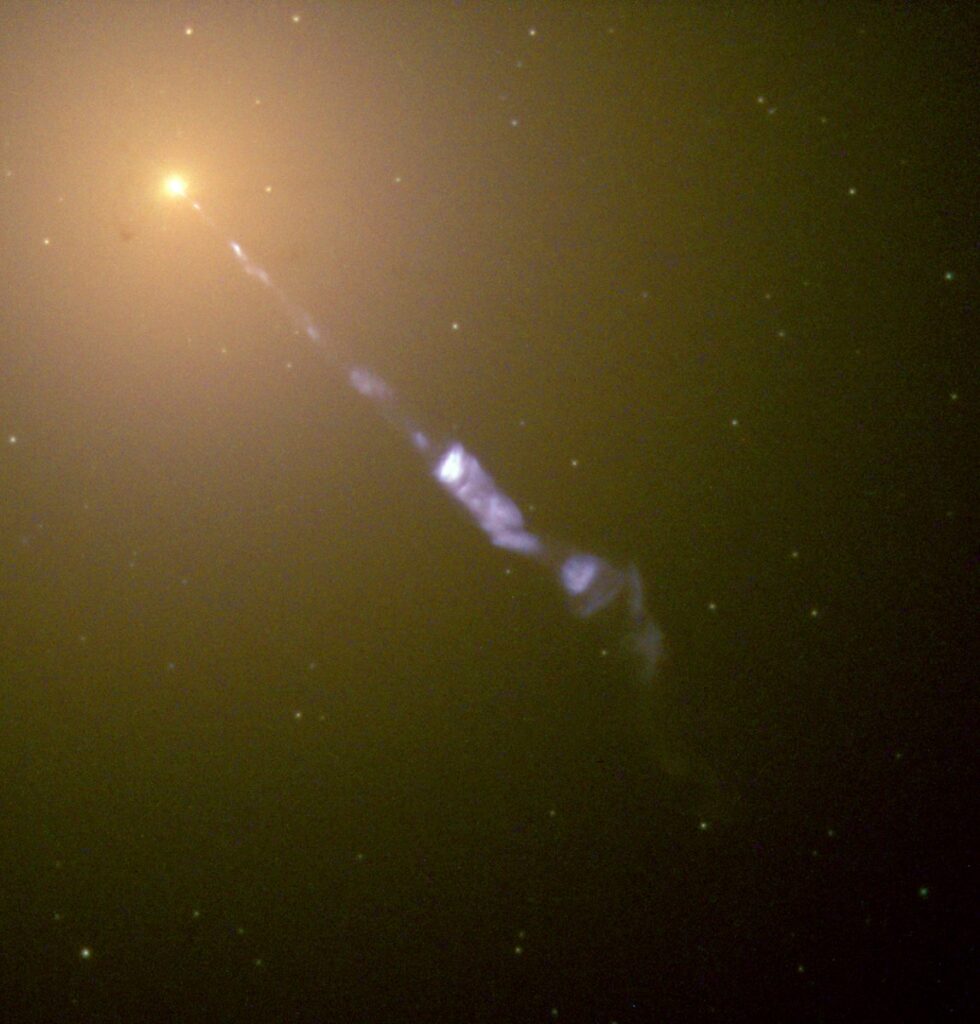

This category is quite a bit different from the ones we have explored so far. Unlike all the previous galaxy types, Active Galaxies are not defined by their shapes. Instead, they are any galaxy whose center is more than 100 times the combined light emanating from its stars. This phenomenon is believed to be tied to the galaxy’s supermassive black hole.

More specifically, the supermassive black holes of Active Galaxies seem to form an accretion disk from the gas and dust collecting around them. The incredibly strong gravity in the region, then, proceeds to compress and heat said disk, causing it to send out large amounts of light that ranges from infrared to X-ray in its wavelength. Furthermore, since shape has nothing to do with this category, any previous types could also be an active galaxy. However, this is pretty rare, as 90% of galaxies do not fall under this umbrella — our own Milky Way, included.

There really is a lot to cover when it comes to Active Galaxies, much more than what we could feasibly get to in one capsule. However, before moving on from this topic, let’s take a brief look at some of the different types. Or would sub-types be a more apt word here?

Quasars

To start off this section, let’s talk about the most luminous type of Active Galaxy, the Quasar. The energy they emit is so strong, in fact, that it is thousands of times greater than that of the Milky Way. However, due to their high luminosity, they are ideal for studying the evolution of black holes and galaxies. Especially since they range from 600 million to 13 billion light years away, providing quite a spectrum of galaxies for scientists to analyze. However, due to the incredibly high energy output needed to fuel Quasars, galaxies are believed to only exist in this state for up to 10 million years.

Blazars

Similar to Quasars, Blazars also emanate large amounts of light. However, what sets them apart is that the latter’s jets are aimed almost directly towards Earth. This leads to them being the brightest — but not most luminous — Active Galaxies observed by us. And, thanks to their brightness, scientists can detect particles like Neutrinos coming from these jets and trace them back to their galaxy. This, in turn, enables them to get a better idea of the environment surrounding a Blazar’s supermassive black hole.

Seyfert Galaxies

To wrap up the Active Galaxy portion of our capsule, we have the Seyfert Galaxies. Named after the American astronomer, Carl Seyfert, who discovered them in 1943, they are the most common type of Active Galaxy. They exhibit the lowest amount of energy and would appear like regular galaxies, if not for the infrared radiation coming off of them. However, some do still emit X-rays. They are also divided into two types: Seyfert I and Seyfert II. The former is characterized by rapid motion near the accretion disk, while the latter exhibits much slower motion in that area.

And before ending this section, I will address the elephant in the room. Yes, all of these photos were taken by the Hubble Telescope.

And that will do it for this year’s first science capsule. I hope you enjoyed joining in on this journey exploring galaxies. Let us know if you would like us to cover this topic more. And before leaving you today, I just wanted to wish everyone a happy new year. Hopefully, the upcoming 2024 will bring lots of joy and wonderful surprises. “See you” all in the next capsule, right here, at impulso.space.