What Makes a Planet… a Planet?

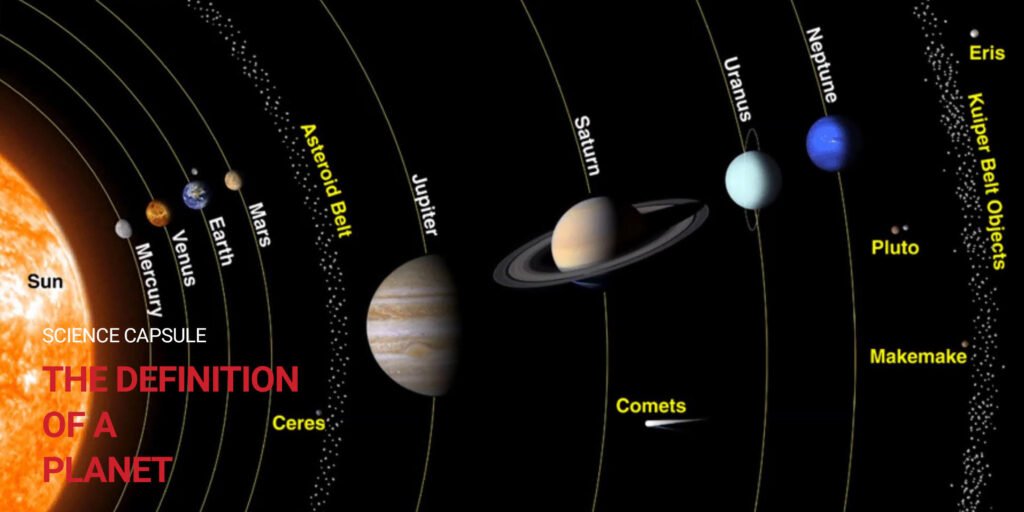

This may appear to be a simple and straightforward question at first. Unfortunately, the answer is anything but. Ever since the field of astronomy arose, scientists have been trying to classify the various celestial bodies into categories. These can include anything ranging from asteroids, meteors, and comets (yes they are all different) to planets, stars, and even galaxies. However, while many of these objects have easily identifiable, specific characteristics, planets are a bit more up to interpretation.

Still, there are some general traits that astronomers have agreed are necessary to identify something as a planet. Mainly they are:

- It must orbit around a star (in our case that would be the Sun);

- Its mass must be enough for its gravity to shape it into a spherical object;

- It must be large enough for its gravity to have cleared away any other objects of similar size around its orbit.

The problem facing astronomers is that, as more is discovered about the Universe, more distant objects have new information unveiled about them. This can then lead to them losing the coveted planet status. In fact, we have already seen some victims of this phenomenon.

The Strange Case of Dr. Pluto and Mr. Ceres

Many of you are probably already aware of Pluto’s recent fall from grace, as it was, once and for all, stripped of the title of planet. However, Pluto is not the first to have experienced this fate. Ceres was another former planet turned-unspecified-celestial-body. And while the demotion of Ceres occurred much earlier than Pluto’s, back in the 1800’s in fact, the reason for both was very much the same.

When these two objects were first discovered, it appeared that they met all the criteria for being deemed a planet. However, as more information arose about them, or, more accurately, around them, astronomers realized that both were lacking in one of the traits. Specifically, other celestial bodies of similar size were in their vicinity. That alone threw into question whether they met criteria number 3.

For Ceres, the discovery of other rocky objects in the area led to the coinage of the term asteroid. This is the type of celestial body that Ceres also falls under. In fact, Ceres was basically the first asteroid to ever be identified.

For Pluto, the question was a bit more complex, thus leading to the decades long debate. Back in the 1990’s astronomers discovered a new region filled with icy bodies orbiting the Sun. This region became known as the Kuiper Belt. And, if you know anything about Pluto, that description of an icy body orbiting the Sun probably sounds familiar. After all, that is basically exactly what Pluto is. And guess what? That’s exactly what a lot of astronomers though as well. This led to Pluto no longer being considered a planet, and instead becoming the largest member of the Kuiper Belt.

The NeverEnding Planet Debate

So, I have a confession to make. The last section of this science capsule was not entirely accurate. Or, rather, it did not give the full picture. While the main reason for the demotion of Pluto and Ceres was their failure to comply to rule 3 of the “planet handbook”, the handbook itself might also have been part of the problem. What I mean is that astronomers had not really agreed upon a final definition for what should be called a planet. The three rules listed before had always applied; however, how astronomers should interpret them was another story.

That is, until 2006. It all started in 2005, when astronomers discovered another large Kuiper Belt Object, Eris. This new object started to raise question as to how it should be classified. And, due to its similarities to Pluto and Ceres, how they should be classified as well. After some debate, it was finally decided, in 2006, that these three celestial bodies would fall under the new category of Dwarf Planets. Since then, astronomers discovered two more dwarf planets, Makemake and Haumea. Furthermore, as many as 100 more are theorized to be in the Solar System alone.

The New Definition of Planet

This new category of dwarf planet, however, brought up a new issue as well. Should we officially change the definition of planet? The answer appeared to be a resounding yes. And this is where the new, standardized “planet handbook” came into play. As I said before, this happened in 2006, after the “birth” of dwarf planets. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) wanted to take this opportunity to update the definition of planets. After all, when they were first discovered, they were known as “wanderers” or moving lights in the sky.

This new definition, therefore, had the aim of being much more specific, so as to reflect the information we had acquired throughout time. The approach they took was to differentiate planets more clearly from other, similar celestial bodies. This led to the definition of the following three categories of celestial bodies (for our Solar System):

- Planets:

- Orbit around the Sun

- Have enough mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces, leading to a nearly round shape (hydrostatic equilibrium)

- Have cleared the neighborhood around their orbits

- Dwarf Planets

- Orbit around the Sun

- Have enough mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces, leading to a nearly round shape (in hydrostatic equilibrium)

- Have not cleared the neighborhood around their orbits

- Are not a satellite

- Small Solar System Bodies

- All other objects orbiting the Sun that are not satellites

The NeverEnding Debate Part II

Unfortunately, as is often the case in science, this new definition was not unanimously accepted by astronomers. Some argued that it was too restrictive and purposely trying to restrict the number of planets. Others thought that a full definition should include the location of the celestial body as well, something that is necessary to understand how our Solar System formed. Others still simply opined that it was not a clear enough definition.

Therefore, yet more possible definitions of planets started to emerge. A somewhat popular one was to define a planet as anything that is naturally occurring and spherical (in hydrostatic equilibrium). However, for distant planets, it is difficult to tell how spherical the object really is. And even disregarding that, the concept of roundness leaves some room for interpretation as well, in terms of how round a planet needs to be.

Yet another proposed definition was one focused around the location of the planet, as well as the material that makes it up. Here, whether or not a planet has cleared its orbit’s neighborhood would not be relevant. Basically, the only consensus that everyone holds regarding planets is that defining them is not as simple as one might think. And so, before I leave you for today, I will come up with my own definition. A planet shall henceforth be defined as: whatever convoluted explanation is needed to have Pluto come back as a planet, while not including the other Kuiper Belt Objects. Why? Because Pluto is named after the Roman God of the Underworld, and he deserves to not get the short end of the stick for once!