Project Gemini

NASA’s major goal throughout the 1960’s was to successfully land a man on the Moon and return them safely to Earth. This, of course, was an unprecedent and not at all simple task. In order to succeed they had to simulate the docking procedures required to dock a spacecraft in space during a Moon landing. They also focused on testing the ability to keep a spacecraft in space for a minimum of 8 days and proving that astronauts could work outside their spacecraft during spacewalks. In other words, their goal was to simulate as many of the conditions necessary for a successful trip to the Moon as possible. That is where the Gemini missions come in.

In order to fulfill president J.F. Kennedy’s goal of completing such a complex task, Project Gemini was started. It consisted in a total of 8 missions, which would ultimately pave the way for a successful Moon landing. But we will talk about this later. The first five Gemini missions had been necessary to put to the test the new spacecraft, determine the feasibility of spacewalks, and demonstrate a successful rendezvous technique. These also led to extending flight durations from 8 to 14 days.

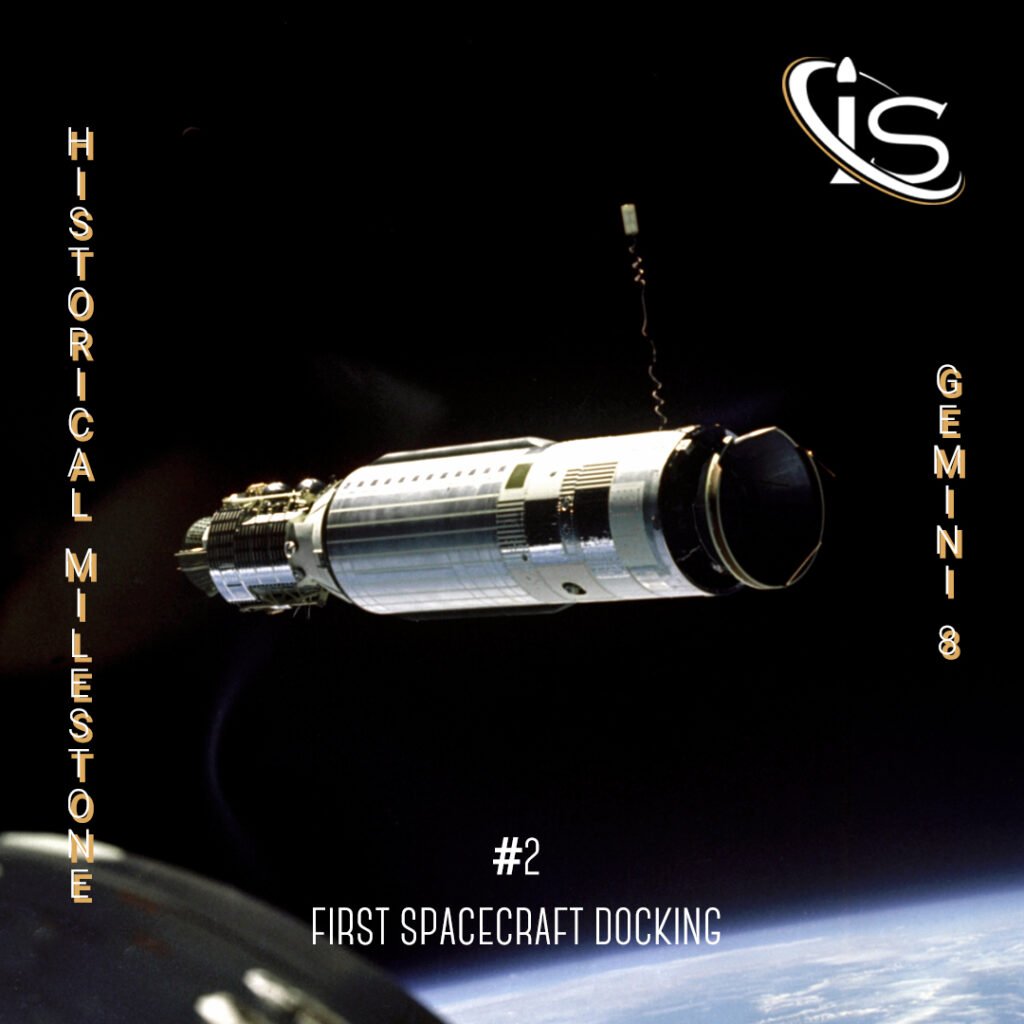

But now, let’s focus on Gemini VIII, the subject of today’s milestone. Its specific goals were docking with a target vehicle, the Agena, and having an astronaut take a longer, more complex spacewalk during a three-day flight. Incidentally, both of Gemini VIII’s astronauts — Neil Armstrong and David R. Scott — would later end up stepping foot on the Moon. Armstrong was the first man to do so, on the Apollo 11 mission, and Scott the first to drive on its surface, on the Apollo 15 one. Interestingly, at the time of the Gemini VIII mission, both were still space rookies.

Preparing for Gemini VIII

The mission was going to start on March 16, 1966. The plan was for Gemini VIII to launch 90 minutes after its target, the Agena. This was done to test Gemini’s ability to dock with a vehicle in space and confirm that Agena was in the correct orbit. After docking, the plan was for Scott to take a 2-hour spacewalk the following day. This would have been the second-ever American spacewalk and a far more involved one than the first — which was performed by astronaut Edward H. White during the Gemini IV mission. Multiple tests were performed the month prior to simulate the conditions of said spacewalk, as well as to ensure the functionality of the equipment.

The Gemini VIII Mission

Finally, the time for Gemini VIII’s launch came. The ground staff helping and communicating with the spacecraft’s crew included space veterans that had flown on previous Gemini missions. One such example was the capsule communicator, James A. Lovell, who was an astronaut on Gemini VII. The launch took place at the Cape Kennedy Air Force Station, currently the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

After lift-off, Armstrong and Scott started their rendezvous with Agena by engaging their thrusters in order to close the gap between the two spacecrafts. First, they established radar contact with their target; then, they were able to spot it at a distance of 87 miles (139 km). After some very careful maneuvering, Armstrong and Scott were finally able to dock with the Agena. The final approach speed at the time of said docking was a very careful 1 ft/s (0.3 m/s). With the docking complete, Scott engaged the Agena thrusters to attempt to roll the combined vehicle by 90°.

Emergency landing

Unfortunately, at this point, things started going poorly for the mission. While passing over the Indian Ocean, Armstrong and Scott momentarily lost communication with the ground due to being out of range. As the Agena was executing a planned maneuver in order to execute the 90° turn, Scott noticed that they had started rolling. Armstrong initially thought of using the Gemini’s thrusters to stop the roll; however, this backfired, making things worse, as there was now a combined roll and tumble motion happening to the spacecrafts. Out of touch with Houston controllers, Armstrong struggled to gain control, with the rate of rotations continuing to increase. It turned out that, due to an electrical short circuit, thruster number 8 was sticking out of position, causing the uncontrolled motions and a rapid depletion of fuel.

Fortunately, Armstrong and Scott were able to undock, disengage the main system thrusters, and engage the re-entry ones. This allowed them to regain control of Gemini VIII. However, since the protocol dictated an immediate landing once the re-entry system was in function, the rest of the mission had to be cut short. This also meant that Scott was not going to be able to perform the much-anticipated spacewalk. Still, the docking was successful and proved that this type of procedure could be achieved in space.

Due to the abrupt nature of the landing, Gemini VIII did not splash down at the designated location. Instead, it ended up in the Pacific Ocean, 500 miles (800 km) east of Okinawa. This was one of the backup splashdown locations that were in place for all crewed missions. Because of that, a team of pararescuers was nearby and ready to intervene when the vehicle did hit the water.

After the Mission

Yes, Gemini VIII was not entirely successful in its goals; however, it did take an important step toward the eventual Moon landing of Apollo 11. The ability to dock Agena in space was crucial in achieving the final goal of getting man on the Moon.

Armstrong and Scott were given Exceptional Service Medals for their effective and heroic response to the mid-mission emergency. President Lyndon B. Johnson organized a Gemini Goodwill tour for Armstrong and Gordon, which spanned 9 Latin American countries. For anyone wondering, Gordon was Scott’s backup on Gemini VIII and would also end up flying on the Gemini XI mission. This was the last NASA mission only manned by space rookies until the Skylab-4 one, in 1973.